Search for lenses, articles and help

Product photographer Phil Sills explores the character of the Cooke SP3 50mm through an unconventional still life series.

The “Cooke Look” has defined cinematic imagery for over a century with its distinctive rendering of light and texture that feels organic rather than clinical. But what emerges when cinema glass meets still life photography? Renowned product photographer Phil Sills undertook an exploration of the SP3 50mm that challenged conventional approaches to both disciplines.

The resulting series, “Bonkers for Conkers,” represents a deliberate departure from commercial still life protocol. Working with foraged natural objects, everyday products, and deliberately dysfunctional items, Sills investigated how the SP3’s character would manifest in a still life environment, discovering in the process a creative freedom that reconnected him with his earliest motivations as a photographer.

Sills’ journey into photography came about through what he describes as “a side door”. Access to a darkroom and a self-taught approach during the film era, unconstrained by formal instruction. “It was all very footloose and fancy free,” he recalls. “There weren’t any rules. I literally just had to teach myself how to do that kind of printing side of it, because it was film. I think that’s what got me into it.”

When he applied to Blackpool’s photography programme, at the time considered one of the country’s premier institutions for commercial photography, the faculty initially insisted on a foundation course. Sills declined. “I just thought, I don’t want to do that. I just want to get going with some photography.” He talked his way onto the course directly.

That combination of self-taught instinct and impatience with convention has defined his subsequent practice. “I don’t follow photographic rules in terms of shooting,” Sills explains. “I don’t really care about the technology side of it. I’m very much like, well, why am I taking this image? And I think that kind of question runs across all my work.” His commercial portfolio reflects this philosophical approach. His images carry narrative weight, suggesting stories and moods rather than simply displaying products.

Phil Sill’s Captivating Still Life Work

The project began with a conversation and a book of still life photographs. Looking through images shot in a naturalistic style, Sills found himself thinking in the opposite direction. “I’ve got to investigate how this lens works,” he reasoned. “So whatever I do, I’ve got to be quite truthful about it and authentic. Let’s just take something that everyone understands. There can be no misunderstanding about what the object is.”

He went foraging. A walk through his local woods yielded conkers, leaves, twigs, and mushrooms, subjects with no commercial agenda. He dried everything in his oven, the smell of a pine forest permeating his house – bliss!

Then he mounted the lens for the first time.

Forest Floor

“I just couldn’t believe it. I was utterly shocked by how different it was to a normal, super sharp, squeaky lens. I just couldn’t believe how much the image changed from the centre to the edges, I was a bit blown away by that. The way focus stretched toward the edges of the frame. The transition from sharp to soft.”

Rather than fighting the lens’s characteristics, he leaned into them: objects placed centrally, textured backgrounds allowed to blur, the full personality of the glass on display.

“It completely started making me shoot in a different way. Put the object central in the frame, and then show what the lens does through either texture or the object going out of frame. Therefore you’re seeing the transition from sharp to that softer interpretation around the edges.”

The Fallen

He set himself strict rules: do what feels natural, don’t question decisions, just act on impulse. And crucially, no post-production or retouching. “I wanted images of value that demonstrate the lens and its qualities. Manipulation didn’t have a place here.”

“Bonkers for Conkers” follows a progression from natural subjects, through everyday products, concluding with a meditation on dysfunction. Each phase explored different aspects of the SP3’s rendering capabilities while developing thematic concerns about consumption, value, and obsolescence.

Meddling

The natural objects, conkers and forest-floor elements, came first. Clean white backgrounds kept compositions focused on the focus fall off. Introducing plastic packaging into these organic compositions added “meddling”, representing humanity’s inevitable interference with nature.

In Flight 1

A Bartenders Tool moves the series into the modern product world. This tool is everyday and basic, with its design being led by functionality. When fully opened though, a change occurs, it becomes more complex and interesting. “The two objects together made me see birds in flight, involved in some kind of mystical dance. The small ties that came off the packaging neatly reenforced angles, twists and turns. They could almost be feathers flying out of the melee.”

In Flight 2

The metallic tray surface gives the image a lift as the light kicks off both the contrasting smooth metal and background texture. There are 2 images, identical in composition, just taken from a different angle. The higher angle demonstrates the drift, blur and ‘stretch’ of the detail towards the edges of the frame, whilst the lower angle brings the viewer closer into the dance of the subjects, making the image feel more intimate.

Broken and Large Bokeh

Broken glass and flask follow, mixing up the object materials, with harder light flaring off metallic surfaces and minimalist fine glass detail. Bokeh is introduced. There is a deliberate blend of texture, light and smooth tone to provide a multitude of interest and eye movement. In camera flare breaks up tone and shifts colour. The broken glass was a fortunate accident before the shoot. It’s not meant to be a commentary on anything, however there is something unsettling about a sharp edge. Be careful.

Tableware

Tableware. An unused prop, sitting in a box. A bundle of raw materials and energy.

We buy something new, open it, put our attention on the thing we want whilst discarding the rest. These shots intentionally beautify both the ‘shiny’ products and the crumpled paper they came wrapped in. One is neither more important than the other. There is a sense of unity and interconnection.

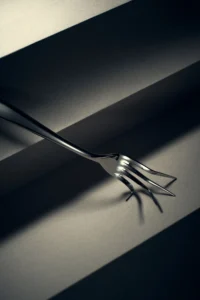

We’re Forked

We’re forked. What does a product become if its primary function is removed? Redundant, quite possibly. Arguably though, the object still has a value even when its original intention no longer exists. Too much in our modern world gets dismissed before its time. Objects, abstracted by environment or by dysfunction have deep and undeniable qualities, hidden, but still available.

Crushed

For the final images, Sills constructed environments from wallpaper, creating claustrophobic stages shaped by texture and shadow. The SP3 continued finding beauty in damage, its characteristic rendering lending dignity to discarded objects.

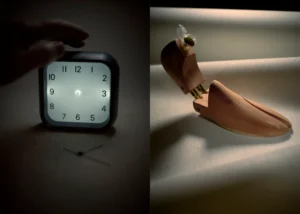

Losing Time and Fallen Tree

Sills shot on a Sony A7R4, choosing the 50mm focal length deliberately. “50mm gives the most natural viewpoint, it’s what your eye expects. Longer than that, everything flattens off too much.” Shooting overhead, a common still life setup, a longer lens would have also meant impractical working distances.

He worked close to wide open, though found for some scenarios the lens performed particularly well around T/4. “Below that it was almost so shallow that for stills, it was like, I’m not sure I’ve got enough sharp.” The shallow depth became a tool for directing attention, letting everything non-essential fall away.

The decision to shoot entirely in portrait orientation was deliberate with Sills considering how images are viewed on mobile phones held vertically and on magazine pages. The consumption metaphor is extended into exhibition.

All lighting was continuous LED, a technique Sills adopted after years of collaboration with film crews. “I used to shoot a lot of drinks photography, which involves capturing movement with fast flash,” he says. “Then I started working with film guys and I went, oh God, continuous is amazing.”

Working without a lens hood represented another departure from still life convention. “Usually I would stick a lens hood over a lens because if I’m firing lights in close quarters into a set, you don’t want anything bouncing around,” Traditional still life photographers would flag everything down, cutting out all flare. Sills let the light play, allowing the SP3’s character to emerge more fully.

The colour work happened in Capture One during the shoot itself with adjustments to shading and coloration in shadows and highlights but with no retouching afterward. “I was twanging everything around, really kind of pushing around shading and coloration, really just messing around with it and just having fun.”

Under the Knife

Sills hadn’t known Cooke before this project, the lenses simply weren’t part of his world. When he mentioned them to his video associates, though, “they just dropped over. ‘Ah, oh my God.’ Very, very famous in that world.” Which was precisely why the project interested him: using cinema glass for something completely different.

“There’s a massive photographic market out there,” he observes. “And photographers think: how do I differentiate myself from everyone else? When everything gets so across the board and so easy to produce, it’s really hard to say, ‘Well, why am I here anymore? What is the point?'” The SP3, he suggests, offers an answer. In a world of clinical perfection, it provides character. “To put this on was just a joy because it felt a little bit more risky. Not quite so drilled.”

“Photographers of this day and age jump much more between film and stills anyway, because it’s much more possible now. I would expect someone coming into the business now to really want to embrace both worlds. And certainly with the cameras and these kind of lenses, you can do it all.”

Bag Less

Looking back on the project, what strikes Sills is the sense of liberation it provided. Commercial work, by necessity, involves principals, client briefs, brand guidelines, the imperative to sell. “Bonkers for Conkers” had none of that.

“It was quite a liberating experience for me,” he reflects. “This reminds me of what I used to do when I first got into photography. When you were too naive and innocent to constrain yourself, you just did whatever you wanted to do. I had no idea what I was doing, literally no idea. And I just found a pathway and carried on with it. I think that kind of thing gets lost when you’re working.”

The lens, in a sense, gave him permission. Its distinctive rendering demanded a different approach, invited experimentation, rewarded impulse over calculation. “I need to be braver now,” Sills concludes. “I need to start saying to clients, ‘I think we should shoot on Cooke lenses.'”

From conkers to bent forks, from forest floors to manufactured dysfunction, the SP3 50mm proved itself in territory beyond its intended use. Which, perhaps, is exactly where character reveals itself most clearly.

See Phil Sills’ Photography at: philsills.co.uk