Search for lenses, articles and help

In the dimly lit screening rooms of Hollywood’s Golden Age, a revolution was quietly taking place. As the talkies transformed cinema forever, one camera emerged to solve the industry’s greatest technical challenge: how to capture pristine images while recording clean sound. That camera was the Mitchell BNC, and today, a rare complete specimen resides in the Cooke Gallery in London—a living testament to cinema’s technological evolution and the artistry it enabled.

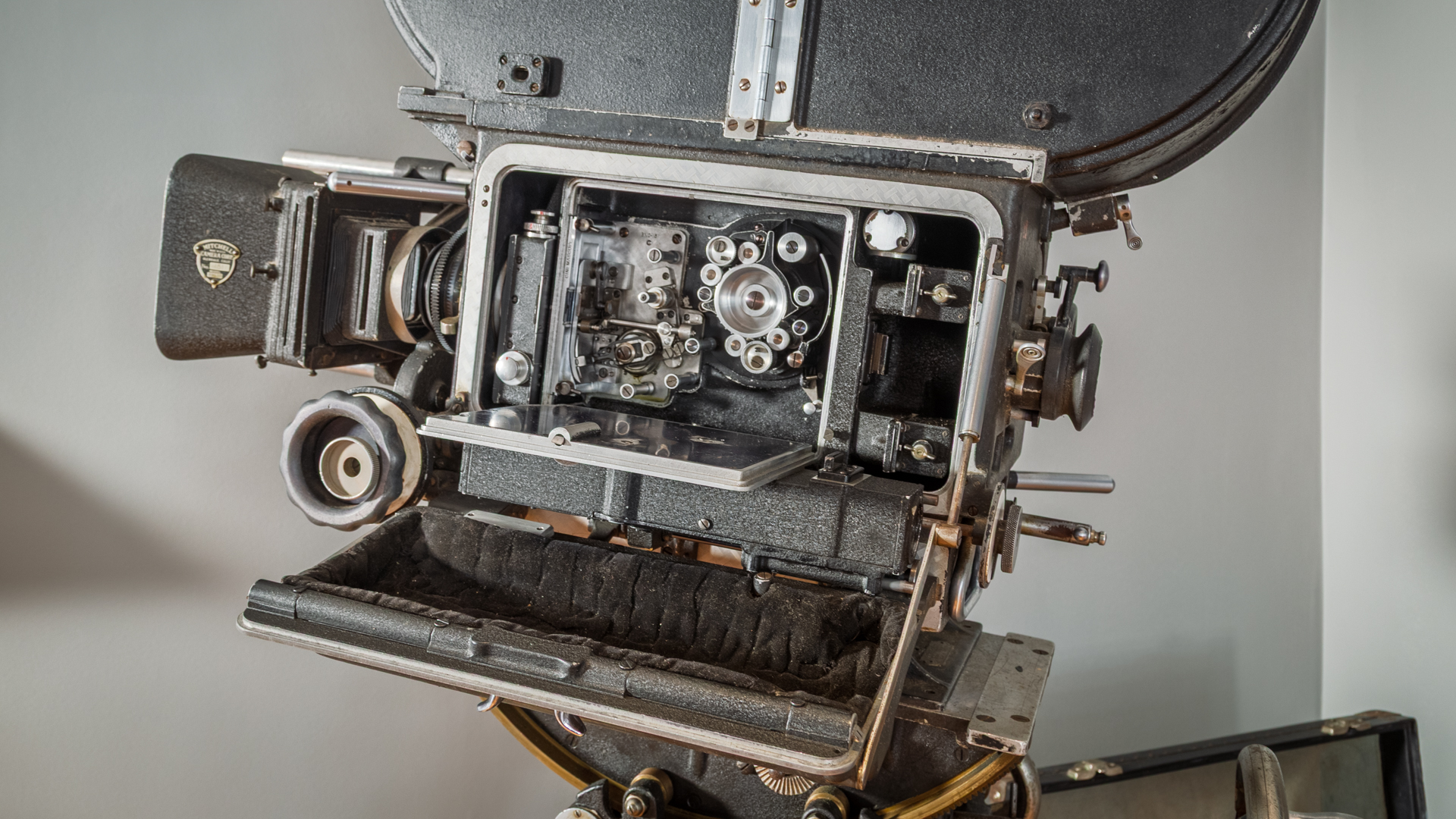

The Legendary Mitchell BNC proudly on display at the Cooke Gallery, London

When movies found their voice in the late 1920s, cinematographers faced a crisis; their cameras—mechanical marvels that had captured the silent era—were suddenly technological liabilities, their mechanical chatterings and whirrings ruining sound recordings.

The industry’s first solution was drastic: cameras were imprisoned in soundproof booths, effectively killing the camera movement that had been evolving through the 1920s. Directors and cinematographers found themselves creatively handcuffed just as cinema was experiencing its greatest transformation.

Enter the Mitchell Camera Corporation and their answer to this dilemma: the Mitchell BNC. The “B” stood for “blimped” and the “N” for “noiseless”—together representing a quantum leap in camera technology that would set the gold standard for decades to come.

With the magazine blimp door open the soundproofing inside is clearly displayed

The Mitchell Camera story began with a naval veteran named George Mitchell who joined the LA Camera Company around 1913. Working there, he encountered John E. Leonard, whose 1917 patent for a metal motion picture camera would change the trajectory of film technology. Impressed by the superiority of metal construction over the wooden cameras of the day, Mitchell saw the future.

By 1919, Mitchell and business partner Henry Boger founded what would become the Mitchell Camera Corporation in Hollywood (initially called the “National Motion Picture Repair Co.”). Between 1920 and 1924, they produced their first camera—the Mitchell Standard Studio Camera—based on Leonard’s design. This hand-cranked marvel quickly captured Hollywood’s attention, with the first unit being sold to the Jackman brothers, a director and cameraman team at Warner Bros. Fred Jackman served as president of the American Society of Cinematographers from 1921-1923, lending immediate credibility to the Mitchell design.

The camera featured a pioneering “rackover” system that allowed operators to precisely focus through the actual shooting lens before sliding the film gate into position—ensuring unmatched precision in framing and focus. Other technical advancements were numerous and included a four-lens turret with interposed filters and masks; an iris diaphragm that could be moved within the frame; a 170° shutter with automatic fade capabilities; a refined claw and pointer pin mechanism. The 32-tooth sprocket was already used in the Bell & Howell 2719 but adapted to provide rock-steady, incredibly reliable operation.

In 1925, Mitchell introduced the Model B with a high-speed mechanism capable of capturing 128 frames per second for dramatic slow-motion effects, further expanding cinematographers’ creative options.

The Mitchell cameras quickly competed with the dominant Bell & Howell models from Chicago, expanding their influence beyond Hollywood’s borders. When Fritz Lang and cinematographer Karl Freund shot the groundbreaking “Metropolis” (1927) in Germany’s Babelsberg studios, they relied on two Mitchell cameras to realize their revolutionary visual style.

As the talkies revolutionized filmmaking starting in 1926, the industry desperately needed quieter cameras. The Mitchell cameras of the time, while less noisy than competitors, still required enclosure in a soundproof booth or oversized blimp (a custom-made box) to prevent mechanical noise from being picked up by sensitive microphones.

In 1932, Mitchell introduced the NC (Newsreel Camera), featuring an improved silent feed mechanism—the NC Eccentric movement with four claws and two pointer pins moving on an eccentric axis. This mechanism provided rock-solid stability while minimizing noise, and its design excellence was such that all future Mitchell cameras would incorporate this system. Between 1932 and 1946, 356 NC models found their way into professional hands.

The rock solid internal mechanism

But the true breakthrough came in 1934 with the introduction of the Mitchell BNC. Rather than requiring a separate blimp enclosure, the BNC integrated the soundproofing into the camera’s design itself. While still substantial in size, it was remarkably portable compared to the soundproof booths that had imprisoned cameras at the dawn of talking pictures. The BNC was a masterpiece of engineering integration—packaging advanced optics, near-silent operation, and exceptional stability in a single unit. Crucially it allowed camera movement to once more be part of visual storytelling.

Director Orson Wells (left) and Cinematographer Greg Toland ASC surrounding the Mitchell BNC camera on the set of ‘Citizen Kane’

The camera was so revolutionary that when the first two units (serial numbers 001 and 0002) were delivered to Samuel Goldwyn Studios in 1935, they were immediately claimed by cinematography legend Gregg Toland, ASC. Toland would go on to shoot some of cinema’s most visually influential masterpieces with his BNC (serial #002), including “Citizen Kane,” “Wuthering Heights,” “The Grapes of Wrath,” “The Long Voyage Home,” and “The Best Years of Our Lives.”

Production of these cameras ceased during World War II, making the early serial numbers particularly significant in cinema history.

With both the operator side blimp door and mechanism door open it’s apparent how closely fitted the blimp is to the camera

The viewing system was equally innovative. Like other cameras of its era, the BNC utilized a parallax side viewfinder system. On the viewfinder, operators could adjust internal framelines for different aspect ratios or focal lengths. When necessary or if preferred, the front lens of the viewfinder could be changed to match the taking lens.

The sidefinder with framelines adjustment dials

The “racking over” process was central to the Mitchell’s operation. Since these early cameras lacked the reflex viewing systems found in later designs, operators had to “rack over” the camera so they could view directly through the taking lens, then rack back to place the film plane behind that same lens for shooting. This process ensured precise focus and framing.

The rear of the camera featured technical refinements like an inching knob for the motor. This allowed operators to manually adjust the position of the shutter, which was particularly useful when the camera stopped with the shutter in the field of view. The viewing tube incorporated a light stop that prevented light from traveling back down the viewfinder and fogging the film when the operator’s eye moved away.

The rear of the camera

The BNC magazines differed slightly from NC versions, with longer throats and wider dimensions to accommodate the blimped design. The magazine system featured both feed and take-up sides, with a belt system that could be physically flipped to run the camera backwards when necessary—a capability that proved invaluable for special effects work.

From the mid-1940s to the 1960s, Paramount won more than 70 Academy Awards. Every award came for a film shot on Mitchell BNC cameras.

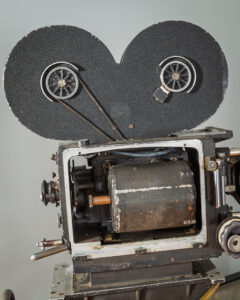

The motor side of the camera with blimp and magazine blimp removed. The ‘Mickey Mouse’ ears magazine on full display with the belt system

The Mitchell camera’s influence extended far beyond Hollywood. In 1944, unable to purchase Mitchell cameras using Pounds Sterling, the Rank Organisation in the UK exploited a remarkable loophole—Mitchell had failed to register a patent in the United Kingdom for the NC design. The Rank Organisation commissioned the Newall company to produce 200 cameras known as the Newall NC, essentially clones of the Mitchell design.

20 Newall cameras were modified in arrangement with Technicolor to use bi-pack film (with double magazines) to film the 1948 Olympic Games in colour, albeit with a limited palette. This process, known as Technichrome, was used alongside three-strip Technicolor and Technicolor Monopack to create a comprehensive colour document of the Games.

The Soviet Union also recognized the Mitchell’s superiority, copying several models either wholly or in part. The Soviets particularly focused on models intended for animation, special effects process plates, or high-speed filming. In some cases, Soviet engineers actually improved upon the original design by adding spinning mirror-shutter reflex focusing and viewing systems, eliminating the need for Mitchell’s traditional rackover focusing mechanism and side viewer.

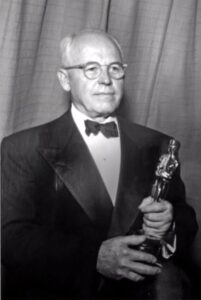

In 1952, George Mitchell received recognition from the Academy Awards for his numerous contributions to cinema technology. True to the engineering mindset that had revolutionized the industry, his acceptance speech was remarkably brief and to the point! “Thank you very much.”

George Mitchell with his Oscar in 1952

The Mitchell continued to evolve over the decades. As early as 1955, Mitchell began converting NC and BNC cameras to reflex viewing systems, creating the first reflexed BNC models. This conversion process continued for nearly a decade, retrofitting most existing units.

By 1967, Mitchell was fabricating brand-new, purpose-built BNCR (Reflex) cameras. These models maintained the same mount principals as the BNC but required specially designed lenses with tapered rear cylinders to accommodate the spinning reflex mirror and as such the BNCR mount was born to differentiate between lenses. BNCR lenses can go on a BNC mount camera, but BNC lenses can’t go on a BNCR camera because of their non tapered rear design.

That same year, Panavision introduced their PSR (Panavision Silent Reflex) cameras—essentially modified Mitchell NC and BNC bodies with custom reflex modifications and improved soundproofing. Panavision’s new PV mount, while similar to the BNCR, featured different specifications including flange depth, port diameter, and locator-pin placements. It also placed the protruding locator-pin on the rear of the lens instead of on the camera port.

Mitchell’s influence extended far beyond the BNC bodies. The company supplied camera movements for Technicolor’s revolutionary three-strip cameras (starting in 1932) and also made 65mm, VistaVision and 16mm systems over the decades. They also developed the Mitchell Pin Registered Process Projector, a background plate projection system with a carbon arc lamphouse synchronized with film cameras. One of the first MPRPPs was used for special effects in “Gone with the Wind,” (1939, dir. Victor Fleming, cine. Ernest Haller ASC) and the technology evolved into two- and three-headed background projectors for VistaVision effects.

Up until the advent of digital technology, the NC and BNC remained critically important for stop-motion animation and effects work. Its rock-solid registration made it perfect for frame-by-frame precision, and the availability of unblimped earlier models at lower costs made it accessible to specialised productions.

After sixty years of innovation, the Mitchell Camera Corporation closed in 1979, but their legacy lives on in the DNA of virtually every professional cinema film camera system used today.

The Mitchell BNC on display at Cooke Gallery represents an extraordinary piece of filmmaking heritage. This particular camera (Serial #151) once belonged to legendary Italian filmmaker Luchino Visconti and was used at Rome’s famed Cinecittà Studios—the heart of Italian cinema.

Luchino Visconti (1906-1976) stands as one of cinema’s most influential artists. Born into a Milanese noble family with close ties to the artistic world, Visconti’s aristocratic heritage would later inform his penetrating examinations of class, power, and decay in European society. His journey to filmmaking began in France, where he worked as a set dresser and later assistant for Jean Renoir, absorbing the French master’s humanistic approach to cinema.

Newspaper Article extract showing Visconti alongside the Mitchell BNC Camera, magazine unblimped for this exterior shot

His 1943 directorial debut, “Ossessione,” (cine. Aldo Tonti & Domenico Scala) arrived like a thunderbolt in Italian cinema. Condemned by the Fascist regime for its unvarnished depictions of working-class characters, the film is today recognized as a pioneering work that helped establish Italian neorealism. During World War II, Visconti’s commitment to his beliefs extended beyond the screen—he served in the anti-fascist resistance and remained politically active in left-wing causes throughout his life.

While beginning as one of the fathers of neorealism, Visconti’s artistic evolution led him toward luxurious, sweeping epics exploring beauty, decadence, death, and European history—particularly the decay of nobility and bourgeoisie. His filmography reads like a catalogue of European cinema’s most visually sumptuous achievements: “Senso” (1954, cine. G.R. Aldo & Robert Krasker BSC) and “The Leopard” (1963, cine. Giuseppe Rotunno)—both historical melodramas adapted from Italian literary classics. The gritty drama “Rocco and His Brothers” (1960, cine Giuseppe Rotunno); and his celebrated “German Trilogy”—”The Damned” (1969), “Death in Venice” (1971), and “Ludwig” (1973).

Visconti’s achievements extended beyond cinema—he was also an accomplished director of operas and stage plays both in Italy and abroad, bringing his meticulous visual sensibility to live performance.

His acclaim was international and enduring. Visconti received both the Palme d’Or (for “The Leopard”) and the Golden Lion (for 1965’s “Sandra”). He received both Oscar and BAFTA Award nominations. Six of Visconti’s films are included on the list of 100 Italian films to be saved—a testament to their cultural significance. His influence extends to generations of filmmakers, including Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, who have acknowledged their debt to his visual mastery.

The camera was acquired in the 1990s by renowned cinematographer Harvey Harrison BSC, whose love for cinema history and appreciation of fine engineering led him to preserve this remarkable system. We are profoundly grateful that Harrison chose our London location to display this true piece of cinema history.

Harrison’s own history is noteworthy. In a career spanning more than five decades, he worked on countless films with some of cinema’s greatest directors and cinematographers. He developed a particular reputation as the premier cinematographer for second unit photography, with credits including “The Kids Are Alright” (1979), “GoldenEye” (1995), “101 Dalmatians” (1996), “The Mummy” (1999), “Lara Croft Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life” (2003), “Sahara” (2005), “V For Vendetta” (2005), “Rambo” (2008), “The Wolfman” (2010), and “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.” (2013), amongst many others. His versatility extended beyond narrative features to music documentaries and concerts films for legendary artists like Elton John, The Who, and Neil Diamond.

Harrison joined the British Society of Cinematographers in 1977 and served as president from 1994-1996. During this period, he was instrumental in forming IMAGO, the European Federation of Cinematographic Societies (officially founded in Rome on December 13th, 1992), and served as its second president from 1994 to 1996, following Luciano Tovoli AIC’s initial leadership. Under Harrison’s guidance, IMAGO expanded to include the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovak Republic, and Switzerland, and the influential IMAGO book “Making Pictures” was conceived. His personal recollections of his remarkable career are published in “Check The Gate.”

Part of what makes our Mitchell BNC display particularly special is the glass that is displayed alongside it. The camera is accompanied by a 7-way set of Series 2 and 3 Cooke Speed Panchro lenses (from 18mm to 100mm) in BNC mount and original housings.

The accompanying lenses, Series 2 and 3 Cooke Speed Panchros

Read more about the history the Cooke Speed Panchro – below is an extract:

1953 – Series II Speed Panchros (S2s) – the aptly named lens designer Gordon Cook began working at Taylor-Hobson in 1948 and embarked on redesigning the Speed Panchro line. In 1953 the 25mm T2.2 was released and by 1958 a complete set of the Series II was available from 25mm to 100mm with stops from T2.2 to T2.8.

The Series II lenses shared much of the DNA of the original Panchro lineage but there was more inclusion of rare-earth glasses and new coating techniques to minimise reflections and increase contrast/transmission performance. Thorium dioxide was added to a silica mixture and helped create glass with high refraction and low dispersion which was massively beneficial in removing chromatic aberration.

This ionizing radiation created “colour centres” on the glass – areas that absorbed some wavelengths of light instead of just passing them through and over time this resulted in a colour cast. Usually this presented itself as a yellow/brownish colour that looked like a tea stain, especially towards the centre of the glass. The 75mm S2 was particularly susceptible to this (the 75mm with the Mitchell BNC displays this prominently)

The 75mm on camera displaying the yellowing

1959 – Series III Speed Panchros (S3s) – Peter A. Merigold designed the Series III lenses. This update covered just two focal lengths – the 18mm Series I was bought up to date with a redesign and the 25mm was upgraded. Both lenses were rated at T2.2 and were some of the first cine lenses to use aspheric optics in their designs. The use of an aspheric surface greatly increased aberration correction in these new lenses whilst also allowing for a decrease in complexity of the optics, thereby reducing the physical size of the lens.

Series II and Series III sets quickly became intermixed with the latter covering the wider end of the focal length range. Over the decades that ensued hundreds of titles were filmed on this combination and they became very popular candidates for lens rehousing.

The 32mm in original housing and BNC mount – note how the iris is adjusted inside of the housing.

We invite you to visit the Cooke Gallery to experience this remarkable piece of filmmaking history in person. Not only can you see the Mitchell BNC up close, but you can actually handle this engineering marvel and understand how it helped create some of cinema’s greatest images.

The Mitchell BNC represents more than just vintage technology—it embodies a pivotal moment when engineering innovation freed filmmakers from technical limitations and enabled new forms of cinematic expression. From Gregg Toland’s revolutionary deep focus in “Citizen Kane” to Visconti’s sumptuous compositions in “The Leopard,” the Mitchell BNC was the instrument through which many of cinema’s defining images were created.

Don’t miss this opportunity to connect with filmmaking history. The Mitchell BNC display coincides with our Brutalist exhibition, now in its final weeks. Visit soon to experience both these remarkable showcases of form, function, and artistic vision.

Proudly on display